84 years ago, a scientist said Earth once had a second moon, which disintegrated into rings like Saturn. He called this little lost moon "Ephemeron".

Recent headlines say Earth has gained "a new moon", & once had "Saturn-like rings". But similar claims have been made before. It's a story stretching from tropical glaciers to plate tectonics...

Hi, I’m Thomas Moynihan. I am interested in the history of ideas, or, how worldviews transform over time. You can read more about me here. I’m using this blog to publish interesting & peculiar gems from my travels in the archives: whether it’s digging up beautiful old science illustrations or posting about forgotten theories I’ve stumbled upon that seem ridiculously strange today. Please consider subscribing. Enjoy my first post!

Last week, there were headlines claiming new evidence had been found that our planet, like Saturn, once had rings surrounding it. This week, it is being reported that the Earth has, transiently, caught a ‘second moon’.

Second moons and Saturn-like rings. Surprisingly or unsurprisingly, this is not the first time such announcements have been made. Eighty-four years ago, in 1940, one scientist proposed them both in combination. He claimed that, long ago, Earth had a second moon. But this later broke up, causing our planet to temporarily gain a ring of debris, some 200 million years ago.

This Sunday (September 29th, 2024), NASA scientists announced our planet has captured a “mini-moon” in the form of the small asteroid called ‘2024 PT5’. It will stay with us until around November 25th, after which it depart us and will head on its way.

In an unrelated turn of events, several days beforehand, new research was published—by Andy Tomkins and colleagues at Monash University—theorising that Earth was once circumscribed by a ring of swirling debris.

Tomkins’s publication attempts to explain what is known as the Ordovician impact spike. This was a period, around 466 million years ago, when our planet suffered a period of peculiarly intense bombardment by meteorites. It was a time when Earth was populated mainly by squids, trilobites, very primitive fish, and ‘sea scorpions’.

Noting that most of the craters from this bombardment cluster around the equator, Tomkins proposes this clustering can be explained by the existence, long ago, of a Saturn-like ring surrounding our planet. This was formed after Earth captured a large asteroid, which was then torn apart by tidal forces, forming a planetary circlet of debris. The infalling of these debris—dragged down by gravity—would explain the equatorial clumping of the impact sites, around our planet’s belly.

Moreover, Tomkins and his team speculate that this “ring system” could have influenced planetary climate. The ring’s proposed existence, that is, coincides with a period of dramatic global cooling known as the Hirnantian glaciation or Early Palaeozoic Icehouse. This chilly period could be elegantly explained by the ring casting its shadow on Earth: obscuring incoming sunlight.

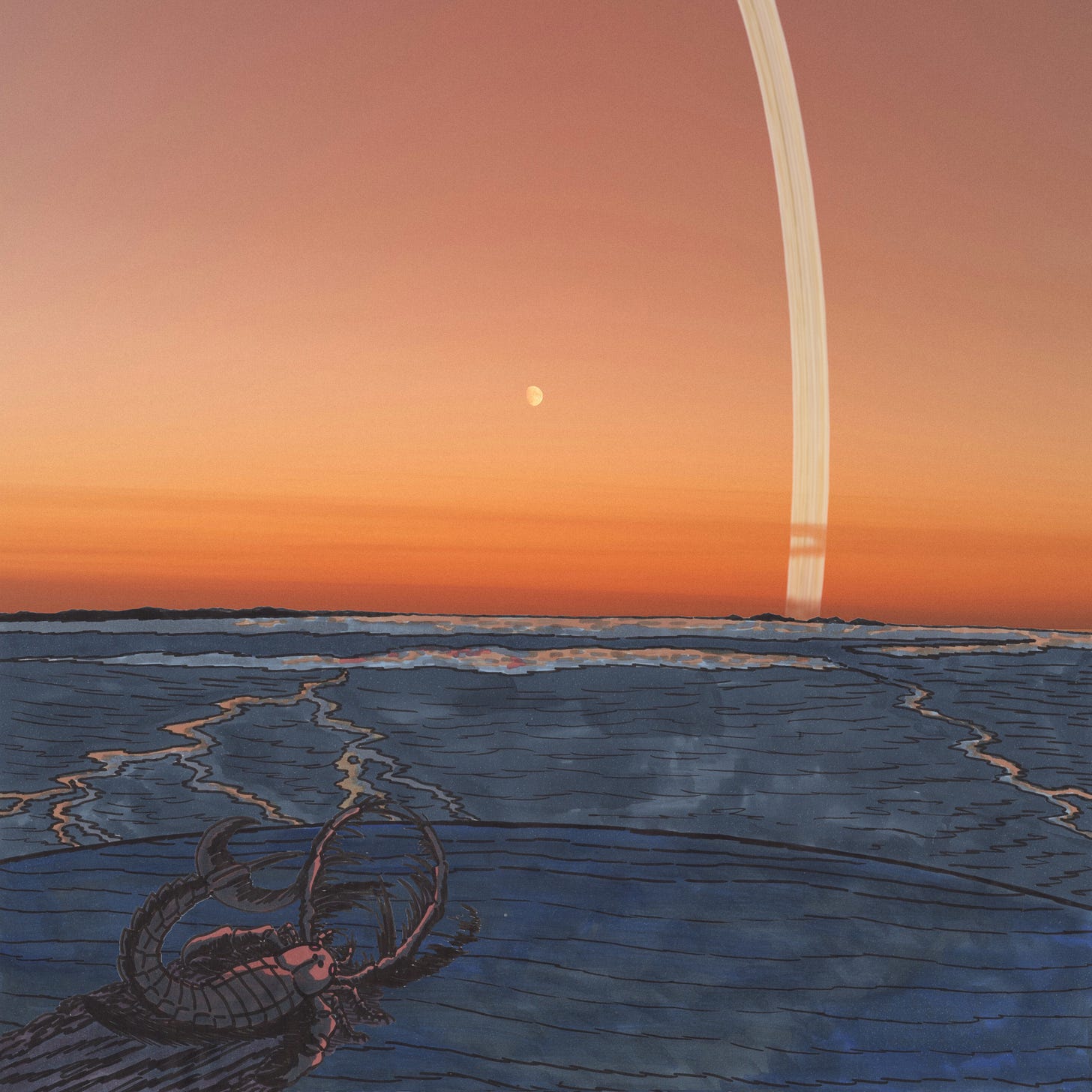

Almost immediately, paleoartists began visualising the scene: when, 450 million years ago, Ordovician arthropods looked wistfully at sunsets bisected by a planet-girdling halo.

It is an elegant and exciting theory. Strangely enough, something very similar has been proposed before. This time, however, it was put forward as an explanation for a slightly later glaciation event, known today as the Late Palaeozoic Icehouse.

In 1940, the geologist Ronald L. Ives published a paper titled ‘An Astronomical Hypothesis to Explain Permian Glaciation’. In it, Ives sought for an explanation for geologic evidence of very ancient glaciers found throughout the tropics, namely central and South America, Australia, and India. At the time, it was thought that this meant that, near the end of the Permian period, multiple hundreds of millions of years ago, icy glaciers somehow flowed away from the equator rather than towards it.

We now know that we find evidence of Permian glaciers in places like Brazil because of continental drift. These landmasses were once much nearer the South Pole. But, in the early 1940s, the theory of plate tectonics was still not accepted widely.

So, Ives sought another explanation for the bemusing fact that available evidence seemed to imply that ice had crept outward from the tropics, rather than downward from the poles. Ives does mention the theory of “continental rearrangements” in his 1940 paper, but puts it neatly aside as a highly speculative explanation—far from settled science.

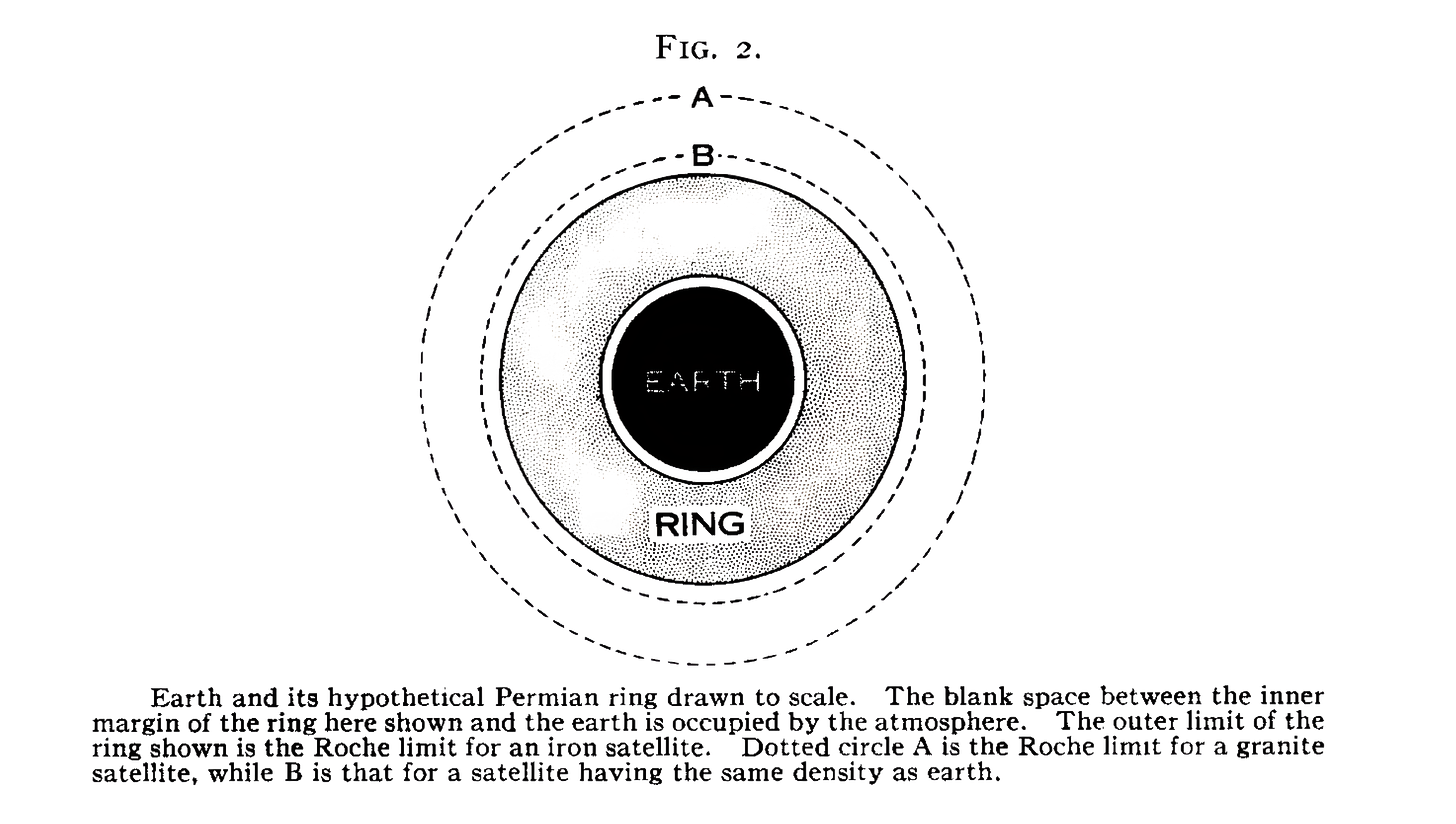

Ives, instead, put forward what he called the “Ring Hypothesis”. This supposed that our Earth, since its birth, had owned two moons. One is the one we still know and love today. The other, occupying a shallower orbit, he called “Ephemeron”. This ephemeral moon, Ives explained, entered Earth’s Roche limit during the Permian period, and was quickly torn up by tidal forces.

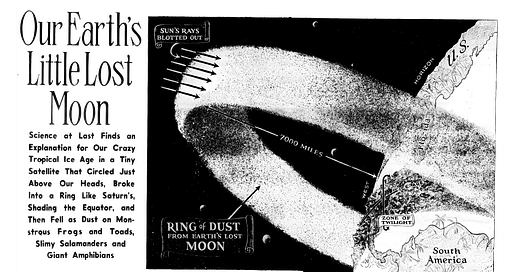

The resulting, very thick ring of debris—in low orbit, at a height of 7,000 miles—would have almost completely blocked sunlight to the tropics. Hence, why, as Ives thought, the creeping glaciers counterintuitively spilt outwards, across the globe, from the Earth’s equatorial belt.

Finally, Ives explained that these remains of Ephemeron—roiling in their orbital swirl—would have ground themselves up, smaller and smaller, before falling to Earth in the greatest meteor shower our planet has ever seen. Hence, the Equatorial Icehouse ended: the tropics became tropical again.

Looking to the “very distant future”, Ives imagined that the Earth may once more “capture some wandering mass of cosmic junk and again acquire a ring like that postulated to explain the Permian glaciations”.

Though forgotten now, Ives’s theory caused enough of a stir to be featured in newspapers, complete with lavish illustrations. In January 1941, The American Weekly ran a story on his speculations.

Elegiacally, it described the late Permian scene at the tropics:

“Daytime would be merely twilight time. There would be no sun in the sky and only a dismal, dull haze as in a desolate, grey day of Winter. The bands would have been like a thick umbrella.”

The article closed with speculation on what would happen if, in some distant future, our current moon should get dragged back toward Earth. At the time, scientists believed this might happen in billions of years. The article pictured our lunar companion breaking up, creating not just a ring of dust, but a world-engulfing “umbrella”. The whole globe, the article continued, will become “a giant ice-box unfit for human and animal life as we know it”.

Perhaps humans will be extinct by then, the American Weekly concluded, or “if Homo sapiens persists” then “advance in learning may be sufficient to combat this hazard”. Otherwise, we learn, “the way out will be to burrow deep within the Earth and create underground cities in the remnants of the Earth’s interior warmth”.

Ives’s theory has not stood the test of time. In the 1960s, plate tectonics became consensus, explaining why evidence of ancient glaciers can be found in the tropics. No longer did we need to postulate secondary moons and Saturn-like rings.

Even if it is just an echo in the history of scientific theories, it is at least intriguing that we are, in 2024, again postulating the prehistoric existence of planet-girdling rings. And, what’s more, rings are once again being conscripted to explain changes in Earth’s climate throughout the deeper past.

What’s for sure, from looking at how much theories have developed in just the recent past, is that we still know far from everything when it comes to the Earth system and its history. For Ives, only 84 years ago, the notion of continental drift was like a “jigsaw puzzle of which some of the pieces are lost”.

It is fascinating supposing what pieces of the jigsaw that is our theory of this world currently lie just beyond our purview. Pieces which, upon discovery, would also dramatically reorganise our sense of things, just like continental drift did a few generations ago.

For my part, I hope Tomkins’s Ordovician-ring theory is true. It is peculiarly salutary to imagine ancient sea scorpions pondering a haloed horizon…

If you enjoyed this, please consider subscribing! I am going to be posting gems I find on my travels through the history of ideas here. Subscribe for weird theories from the past & beautiful illustrations of retro-science. Thanks!

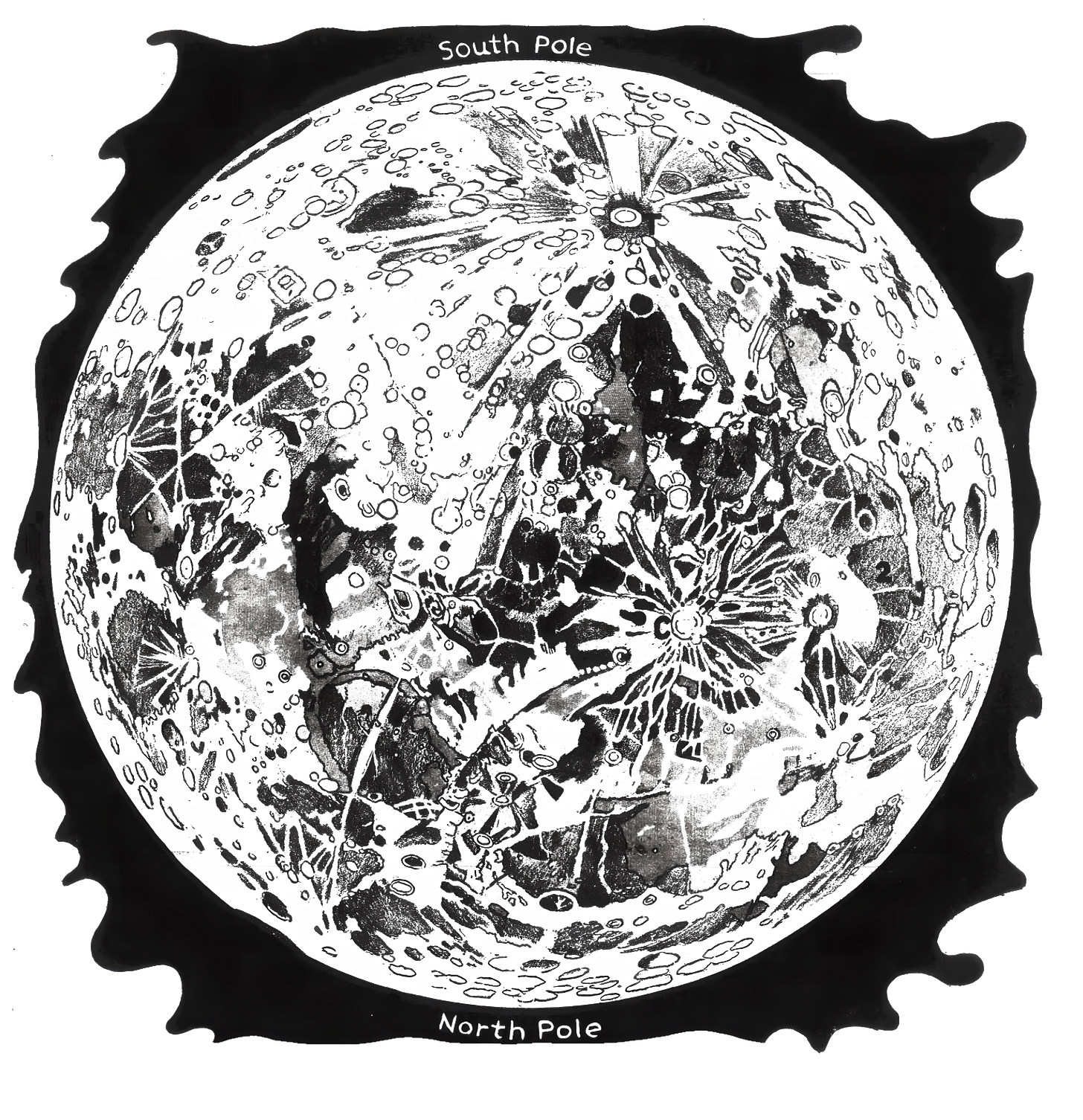

PS — Beautiful bonus drawing of our moon, done by the same illustrator who provided the artwork for the American Weekly article quoted above, from 1929: