From Victorian time capsules to Soviet plans to drain oceans — A wrap-up of 2024

A collection of things I published throughout 2024!

The year 2024 was a memorable one. Giving talks and partaking in discussions, I travelled from Beirut to Boston to the Brecon Beacons — speaking in Gothic castles, in Remonstrant churches, and Venetian palazzos. A big thank you to all the fascinating people I met and learnt so much from.

Below is a selection of some of the essays and pieces I published this year, in chronological order.

1 — ‘What the “future histories” of the 1920s can teach us about hope’ — for BBC Future

12 Jan 2024

An exploration of visions of the future from a collection of books published a century ago: the ‘To-Day & To-Morrow’ series. Each entry in the series would task an intellectual or expert to detail their forecast for a specific domain of life. Topics ranged from the future of swearing, to those of poetry, nonsense, and monogamy. In this essay, I explore how these books somehow managed to avoid the restrictively dyadic future-thinking of our own time, which too often is forced into a binary straitjacket of ‘utopia’ versus ‘dystopia’. In the decades since, and following the various disillusionments they provoked, we’ve lost some of the nuance these old prophesies managed to muster: hence, these tomorrows of yesterday can still teach us a lot today.

2 — ‘A US engineer had a shocking plan to improve the climate – burn all coal on Earth’ — for BBC Future

1st Feb 2024

I was shocked when I first tracked this down in the archive. That’s saying something, as I see my job as digging up the outlandish things people used to think. The short article tells the long-forgotten story of William Lamont Abbott, a US engineer who, upon learning about the Greenhouse Effect, thought it would be a great idea for humanity to set alight to all the coal seams on planet Earth simultaneously. He thought that this would provoke a return to Edenic weather: creating tropical conditions all the way to the poles, allowing greater crop yields for a rapidly reproducing humankind. He toured the US in the 1920s, proselytising his pyromaniac creed. What’s more, he wasn’t alone. This is yet another lesson in caution from history: when humans gain new knowledge about the external world (e.g. that coal-burning warms the atmosphere), they don’t always immediately arrive at the correct practical conclusions when it comes to global priorities… In fact, it seems they are often not only wrong, but catastrophically wrong.

3 — ‘Untangling religion from our AI debates’ — for Noema Magazine

27th Feb 2024

The question of ‘AI & religion’ — as with AI combined with almost any other domain of life — is probably only going to spill more ink and produce more scribbling as time passes. To me, the question seems vexatious. You’ll often hear people claiming that this or that ideology or group in the vicinity of AI research is practising something like ‘a secularised religion’. It’s not only here, you increasingly hear such claims made in politics too. Notably, it’s almost always used as an insult. This strikes me as peculiar. So, I wanted to shed some irenical light on the matter: trying to soberly respond to the question of theological residue in AI discourses productively, rather than merely with the attitude of a debunker or adversary. Yes, ideas like ‘superintelligence’ clearly resemble theological ideas — ones, tellingly, from the Abrahamic tradition — but what do we do with this beyond sling more mud and sharpen more barbs?

4 — ‘If a Victorian historian had his way, there'd be a giant time capsule under Stonehenge’ — for BBC Future

9th Jul 2024

This was a fun one — I also did the lead illustration! The article tells the story of the eccentric and endlessly fascinating Victorian historian Frederic Harrison. Being a historian, he had a good sense of time: not only in the retrospect, but also the prospect. Highly sensitive to how the past is a foreign country, he presciently looked forward to an unfamiliar future, too. He described his time as one occupied by “historical consciousness” to a degree more than any before: that is, to the anxieties of how they would be recieved by posterity. Knowing his era couldn’t control the opinions of future generations, he endeavoured to at least retain the fidelity of the picture of Victorian life that would be passed on. To that end, he decided to put a giant time capsule underneath Stonehenge (a place unlikely to be tampered with too much), and fill it with a snapshot of his epoch… one complete with the skeletons of animals which Harrison predicted wouldn’t survive the onslaught of Victorian acquisitiveness.

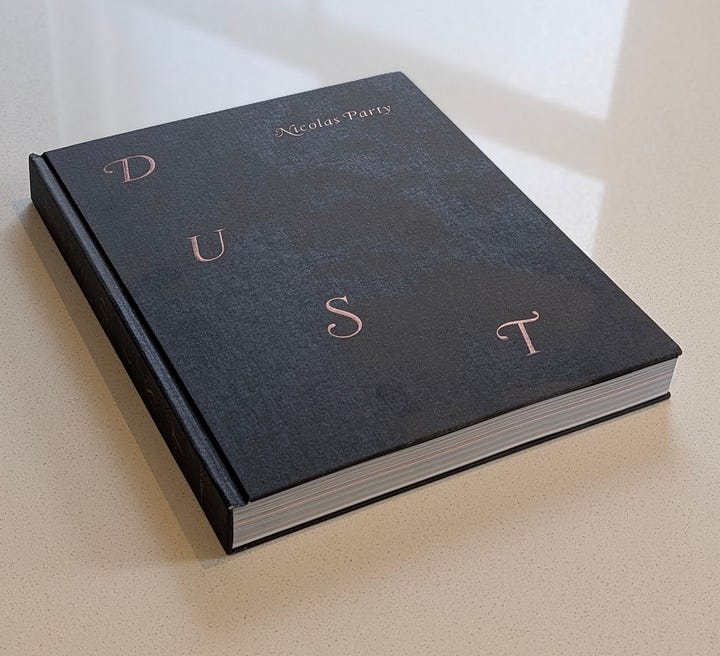

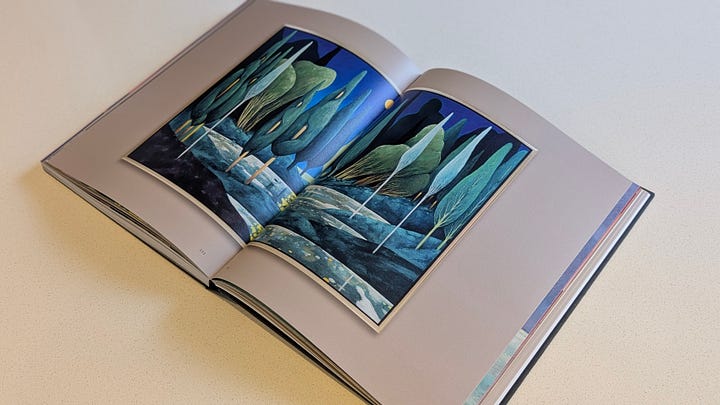

5 — ‘The Mortality of Immortality’ — for Nicolas Party’s ‘Dust’ Exhibition at South Korea’s Ho-Am Museum

31st Aug 2024

I am a big admirer of Nicolas Party’s paintings and pastel murals: I find both the subject matter and style very evocative. After speaking together on a podcast for the Atlantic magazine, Nicolas kindly invited me to write an essay for his most recent exhibition, ‘Dust’, at South Korea’s Ho-Am Museum. It was a serious pleasure to be translated into Korean for the first time! The itself exhibit looks stunning: I was proud to scribe an essay for the accompanying catalogue, musing on Nicolas’s chosen themes of transience, longevity, and mortality. My essay reflects on the old psychoanalytical theory that civilisation begins with the individual’s “denial of death”, before exploring how such psychological repression connects to historic acceptance of not only individual mortality, but also the mortality of our species and all biological life itself. I will be posting a on my website soon!

6 — ‘How the search for dinosaurs on Venus exposed a climate warning for Earth’ — for Big Think

4th Oct 2024

Over the years, I’ve been shocked to increasingly learn just how many people, in the earlier 1900s, took seriously the idea that Venus might be a swampy planet covered in jungles and, potentially, inhabited by dinosaurs. This, to the contemporary eye, seems patently absurd: surely everyone would know, a priori, this couldn’t be true? But, prior to contrary evidence, such conjectures were very much on the cards. In the first half of the previous century, it was assumed Venus was essentially a ‘younger’ version of Earth, and was thus undergoing something similar to our Paleozoic Period. Hence, the Venusian dinosaurs. The contrary evidence came, crushingly, when the first human probes flew close to Venus: revealing it to be a lifeless hellscape with a scorched, pressurised atmosphere. This article tells the story of how this woke us up to the potential for similar climate catastrophes to unfold on Earth. Searching for dinosaurs on Venus thus provided a warning for our own environmental future on Earth.

7 — ‘Are we accidentally building a planetary brain?’ — for Noema Magazine

19th Nov 2024

I immensely enjoyed writing this one. Put short, it is about how we can blame crabs for all this contemporary talk of the ‘Anthropocene’… In more detail, it tells the story of the American geologist J.D. Dana who from studying crabs in the mid-1800s became convinced that all evolution is tending “headward”. Various lineages of crustacea, he argued, have all converged upon a crab-like form; and what typifies crabs, over and above their more shrimp-like ancestors, is the shrinking of the abdomen, which tucks away underneath an increasingly engorged braincase. Of course, something similar typified our evolution too. From this, Dana thought he had discovered a universal law of evolution: that all nature, all living matter, is trying to reorganise itself into a brain. When people noticed that the recently planted transatlantic telegraph cables — connecting continents like hemispheres of a brain — curiously resembled nerve fibres, many concluded: ‘yes, we are buildling a planetary brain’. The article traces this peculiar thought throughout the 1900s, from Vernadsky to Maynard Smith, recovering some otherwise forgotten figures along the way, before demonstrating how none other than Albert Einstein himself was keen on such ‘world-brain’ ideas.

8 — ‘How humanity discovered we’re all made of “star stuff”’ — for Big Think

18th Dec 2024

In 1973, Carl Sagan memorably said that we are “are made of star stuff”. But he was far from the first. In this article, I tell the story of how we realised the suns are our parents and our bodies are made from their ash. It stretches all the way back to the 1500s, when the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus confidently declared that the stars have “nothing to do” with our bodies. They, he insisted, “are neither party of us nor we of them”. Back then, of course, there was no way of determining the truth of this conclusively. No one had any clue what the stars were made out of. Many believed they were simply made of different stuff entirely: composed of materials not found on Earth, goverened by different laws. Three centuries later, in the 1880s, the French philosopher Auguste Comte declared we would never be able to ascertain the chemical constitution of stars. This didn’t stand the test of time. Only decades later, the field of spectroscopy was founded, implying we are the stars’ corporeal siblings, as we are made from identical elements. But then, throughout the 1900s, scientists realised that the suns are actually our parents: all living things are made from elements forged in ancient stars. Read the piece to find out the full story!

9 — ‘Five books proving history isn’t driven by destiny, but by chance and (sometimes) choice’ — for Shepherd

30th Dec 2024

Shepherd seem to be embarking on an admirable mission: creating a new way to find books and share reading lists. I’m all for that! They approached me to write a list of five books I admire, unified by any theme I choose. So, I went ahead and cooked up a list of books that, as the title suggests, argue that history — broadly concieved — isn’t dictated by destiny, but instead is driven by chance and sometimes choice. I decided to combine my interest in intellectual history (Hacking, Blumenberg) with my admiration for biological history (Gould, Powell). Because, if the greatest story ever told on Earth is that of evolution, then the second greatest might be the saga of our coming to understand and uncover it. What’s more, I also got to nod to Thomas Browne: probably my favourite prose writer, and the Jorge Louis Borges of the 1600s!

Onwards to 2025!